Philadelphia City Paper Feature

Sidewinder

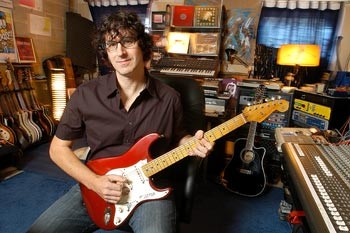

Inside the mind of a serial collaborator Tim Motzer

by A.D. Amorosi

published Nov 1, 2006

Collaboration’s a powerful drug.

Tim Motzer is hooked. Check his credits.

|

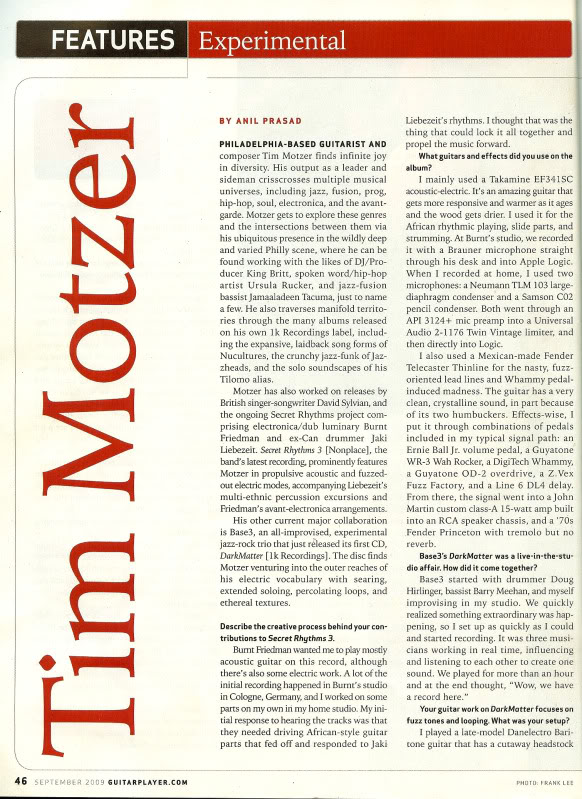

The guitarist/producer has paired with soul men (Kenny Lattimore), avant gods (David Sylvian), house heads (4 Hero) and Afro poppers (Les Nubians). He’s done hip-hop with the Roots, fusion with Jamaaladeen Tacuma and krautrock with Can’s Jaki Liebezeit.

He’s conspired so closely, and so often, with fellow Philly dogs Ursula Rucker and King Britt on so many recordings in so many ways it’s hard to pin down who Tim Motzer really is. Even CP came up with a blurry image of him with Britt when we praised their Sister Gertrude Morgan collaboration on our cover. “I was having a bad hair day anyway,” says Motzer

Motzer’s got his own projects, too: Global Illage, Fractal Ark, Jazzheads and the poetry-infused Secret Voices. So when and where is Motzer most alive? Working on someone else’s music or his own?

He’d rather play than talk about it. “I’m just in it, you know — doing it,” says Motzer. But he’s not just another session guy. “Ultimately whatever I’m involved in gets a big dose of whatever ‘my thing’ is. I mean, I’ve had a blast with solo ambient stuff like Tilomo. But I dig working with others because of the give and take of ideas.”

It’s not like Motzer hasn’t been working on what King Britt told me was a Ziggy Stardust-era Bowie-like solo CD — for nearly three years. “I’ll have a record with my voice under my own name soon,” says Motzer. Till then, there’s a teaser called “Starship” on his MySpace page.

“Everything I do has its own identity. They’re their own universe.” When a true collaboration comes, Motzer gets crazy stimulated. “What occurs is not necessarily about the artist, but a final outcome,” he says. “The art itself goes to a higher place.” He pauses. “Well, we hope so anyway.”

Motzer’s a serious dude.

As a producer, he’d rather catch the moment and find nuance as opposed to perfection. An improvisation-minded player, Motzer wants to take the listener where there’s depth and soul. The Hamilton, Ohio-born composer, whose mom sang in big bands, is the type of guy who talks about Mahavishnu Orchestra and King Crimson.

He got to be best friends with Barry Meehan — his closest collaborator in Fractal Ark and Global Illage — because Motzer had a jam party and Meehan introduced himself by sitting in on bass pedals. A bass-pedal party. That’s his brand of fun.

That’s pretty much how Motzer befriended Britt, by playing guitar at a Back2Basics party at Silk City in 1995. “There’s a special chemistry when we work together,” says Motzer. It was Britt’s enthusiasm for Motzer’s solo album (Soft Lunch, under the pseudonym Tilomo) that encouraged him push it into release. Motzer meant for it to be chill-out music, but it’s a more emotional and complex. “It takes you somewhere. Just don’t drive or operate farm machinery while listening to it,” he says jokingly. There’s a palpable sense of isolation to all that Motzer touches — passionate, but distanced.

His new record, Secret Voices’ No Time for Silence, is mournful. “I find it easier to write with the feel of the dark than the happy,” says Motzer. “I suspect it’s a reflection of having to travel so much.” Most of No Time for Silence was recorded in Italy and Spain.

With Meehan creating bass loops and Italian co-composer Enrico Marani applying layers of drones, No Time for Silence allowed Motzer to add his own loops, drums and layers at will. He was casually planning on adding a few voices. Nothing much. Until, again, the project became about something and someone else. “It evolved slowly into having poets from different cities around the globe collaborate,” he says.

Along with Italian and Portuguese poets — Adriano Englebrecht, Benedicte De Dorlodot — the contributions of Philly’s Ursula Rucker, Elliott Levin and Rich Medina helped contextualize the work. “Their contributions put everything in perspective … a totally natural part of framing out the work.” Suddenly, Motzer goes into overdrive, talking about how Rucker’s poem deals with childhood innocence and hate (“so beautiful and melancholy”) and how Medina improv’d his way through an allegorical work about the war in Iraq and how Levin’s “To Be Perfectly … Frank” was an epic. “It was stellar as it went down in the studio — his three-dimensional poem, his beautiful harmolodic saxophone multitracking. All 19 minutes of him, it’s definitely something to hear.”

In his enthusiasm for other people’s contributions to No Time for Silence, Motzer nearly forgot that it was his record we were talking about, not Levin’s or Rucker’s. “I think my identity may get lost in these actual projects,” he says. “That’s my challenge in the coming years — to get out of the shadows.”

Previous

Previous  Next

Next